Good editing is invisible. Bad editing is painfully obvious—usually because the editor has, instead of clarifying the author’s intent, attempted to rewrite in the editor’s own style. Editors are there to remove, rearrange, and altogether improve, not to make the writing their own.

To illustrate this idea, I will take a piece of writing often mocked as purple prose and use both approaches. The author, long dead, will presumably take no more offense at this than at having inspired both a contest for atrocious writing and a beloved cartoon beagle’s creative pursuits.

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the house-tops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

This is the first sentence of Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel Paul Clifford. Let’s agree that, while the language is evocative, the sentence itself is in dire need of assistance.

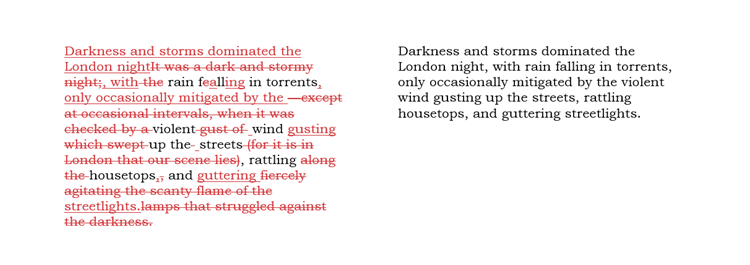

There are two ways to approach this task. The first approach is to completely rewrite the sentence so that it says the same thing but differently. Let’s call this “The Machete Approach” since it involves the near complete deconstruction of the original, and its subsequent reassembly from scratch.

Figure 1. The Machete Approach

The original contains 58 words. The Machete Approach more than halves that total to 28. The result seems familiar but in no way resembles the original. In fact, it reads much more like I wrote it than Bulwer-Lytton.

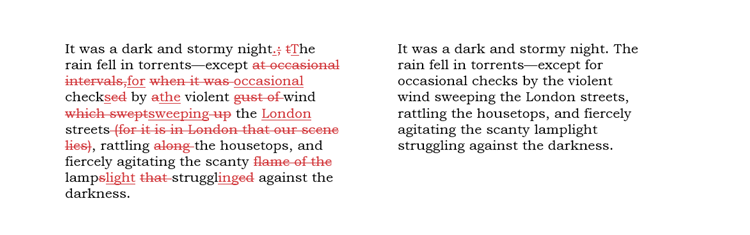

The better approach is to gently improve the flow and clarity while retaining the author’s voice. Let’s call this “The Razor Approach,” since it involves paring extraneous words and phrases while retaining the author’s distinctive voice and style.

Figure 2. The Razor Approach

This second approach is gentler than the first, preserving more of the original word order and choice while still streamlining the content and lowering the word count to 37. More work could still be done, but that begins to encroach on the author’s domain.

Beginning editors sometimes forget that, in the end, it is the author’s name that goes on the work. I’ve learned to think of my edits as suggestions—especially since the writer is not obliged to accept them—so as to not take any rejections personally. (After all, it is the author’s prerogative to be wrong.)

Sometimes, rewriting is necessary. When this is the case, offer recommendations for improvements but leave the changes to the writer. An editor who spends more time with a machete than a razor needs to find some other creative expression than chopping up someone else’s brainchild . . . such as writing an article about editing, perhaps?

This article was originally published by ACES: The Society for Editing.